CORBIN SHAW - NOWT AS QUEER AS FOLK INTERVIEW

Art/Photography

NOWT AS QUEER AS FOLK:

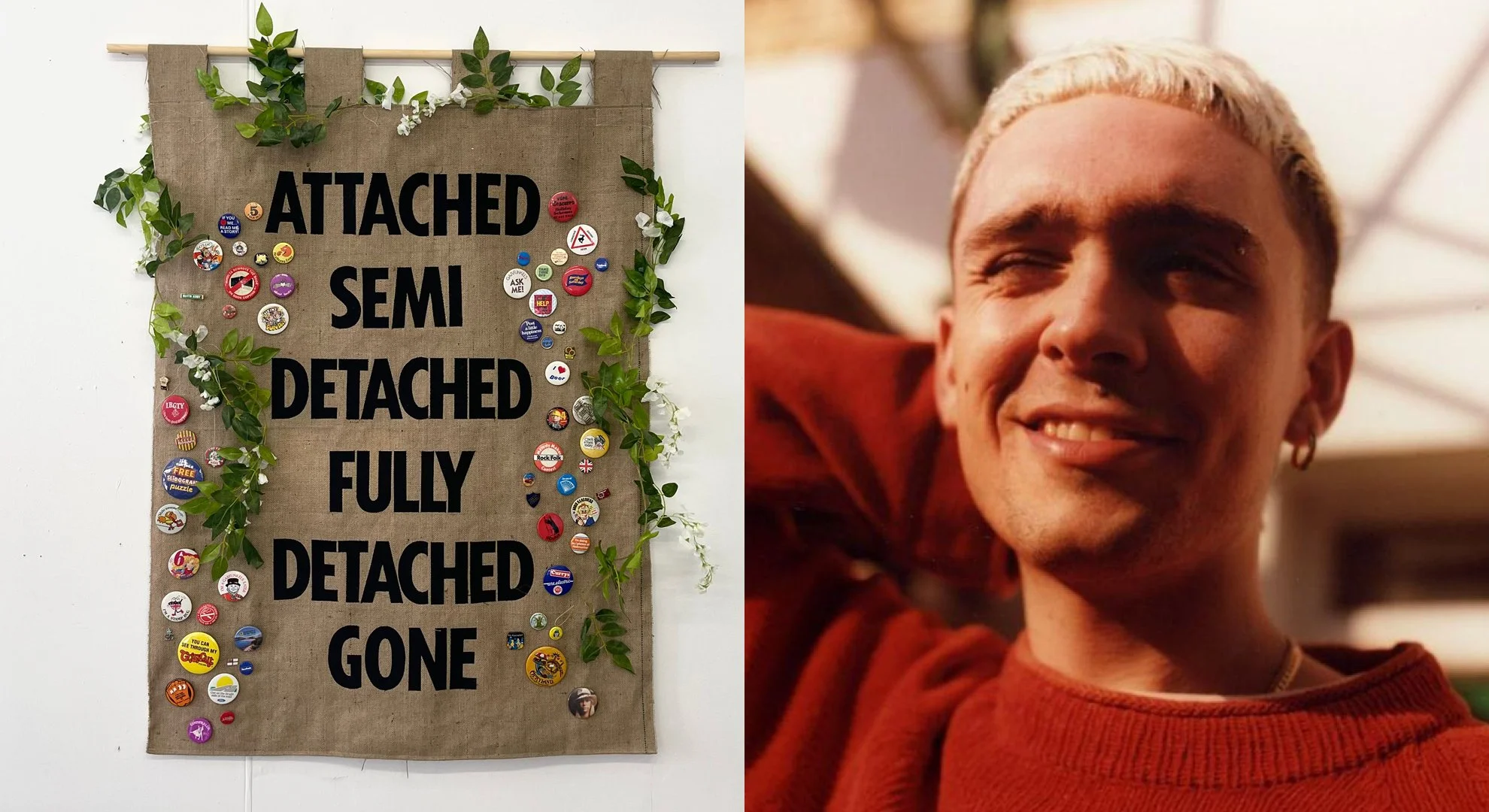

AN INTERVIEW WITH CORBIN SHAW

South Yorkshire’s finest Corbin Shaw spoke with us ahead of his solo show ‘Nowt As Queer As Folk’. The show which pays homage to the folk traditions, kooks and quirks of village life in his home town of Harthill is open from the 10th February, at Guts Gallery HQ, Unit 2 Sidings House, 10 Andre Street, E8 2AA

In our interview, Corbin talked us through his own background and relationship with Folk, the origins and growth of the traditions within his hometown and the wider UK and how he hopes to utilise Folk as a tool to hold a self-reflective mirror to the shared consciousness of modern Britain.

Words:

Luc Hinson

Artwork:

Corbin Shaw

BB: Your show Nowt As Queer As Folk is opening on 10th Feb, tell us a bit about what we can expect to see?

Corbin Shaw: The title of the show translates to nothing is as strange as people. Which is a Yorkshire phrase, and that phrase is a reflection on my relationship to the village I grew up in and the traditions of the village and folk itself as a whole in England.

The exhibition centres around a well in the gallery, which, where I'm from in South Yorkshire just on the border between South Yorkshire and Derbyshire, we have a tradition specific to the areas called the well dressing. And I've grown up watching the Well dressing in my village of Harthill, it was like a pagan ritual to give thanks for the clean water that came into the valleys. It became very popular after the plague and whatnot, which kept a lot of the villages alive.

What people do is they have a board in which they put clay on, and at the turn of the season, when the flowers start to bloom, villages will take petals, and they'll dress the well. There are all these designs and it usually depicts something religious, but it's moved on to be it's quite open now, depending on what village it’s in. When they unveil the dressing of the wealth, the Morris men come and bless the well by dancing next to it.

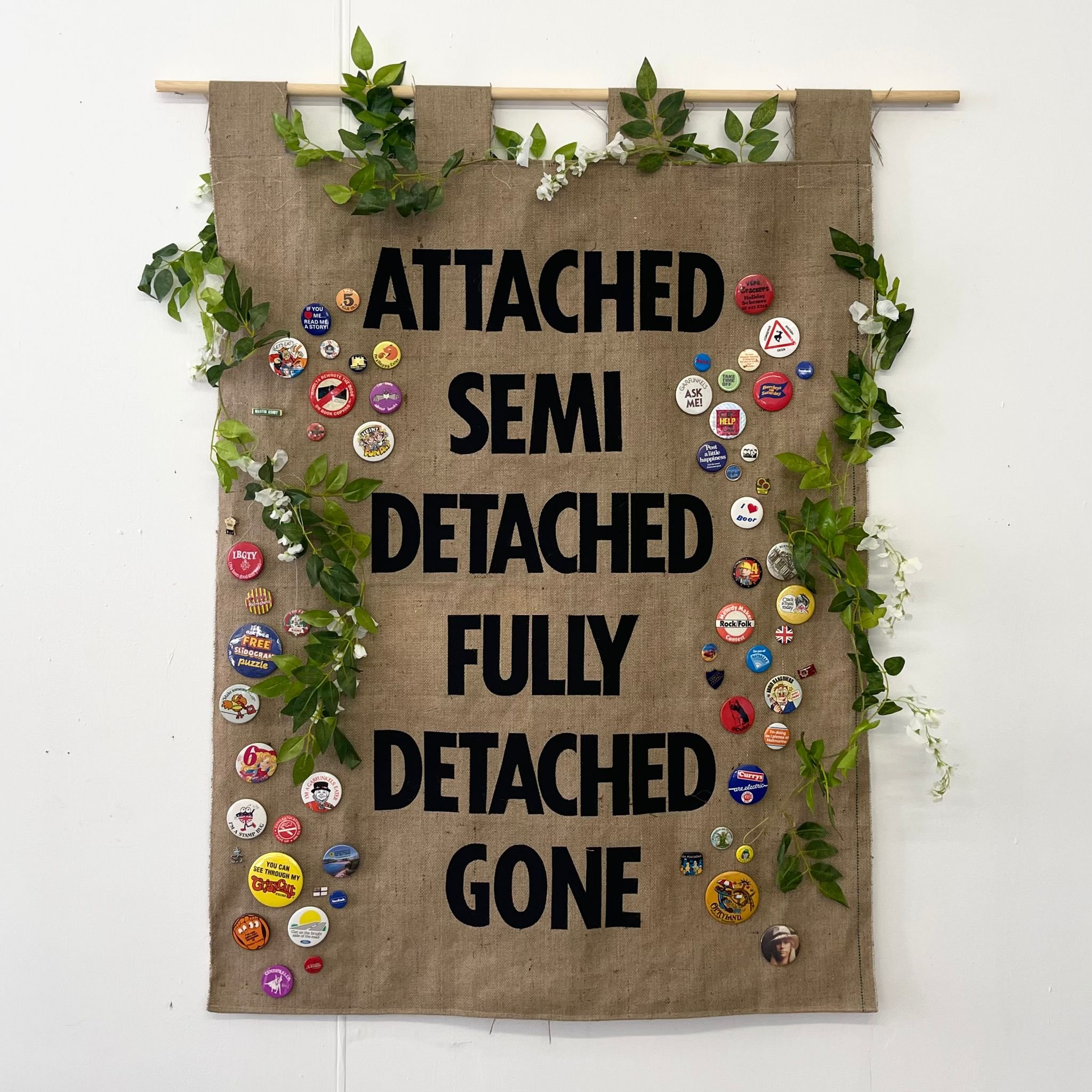

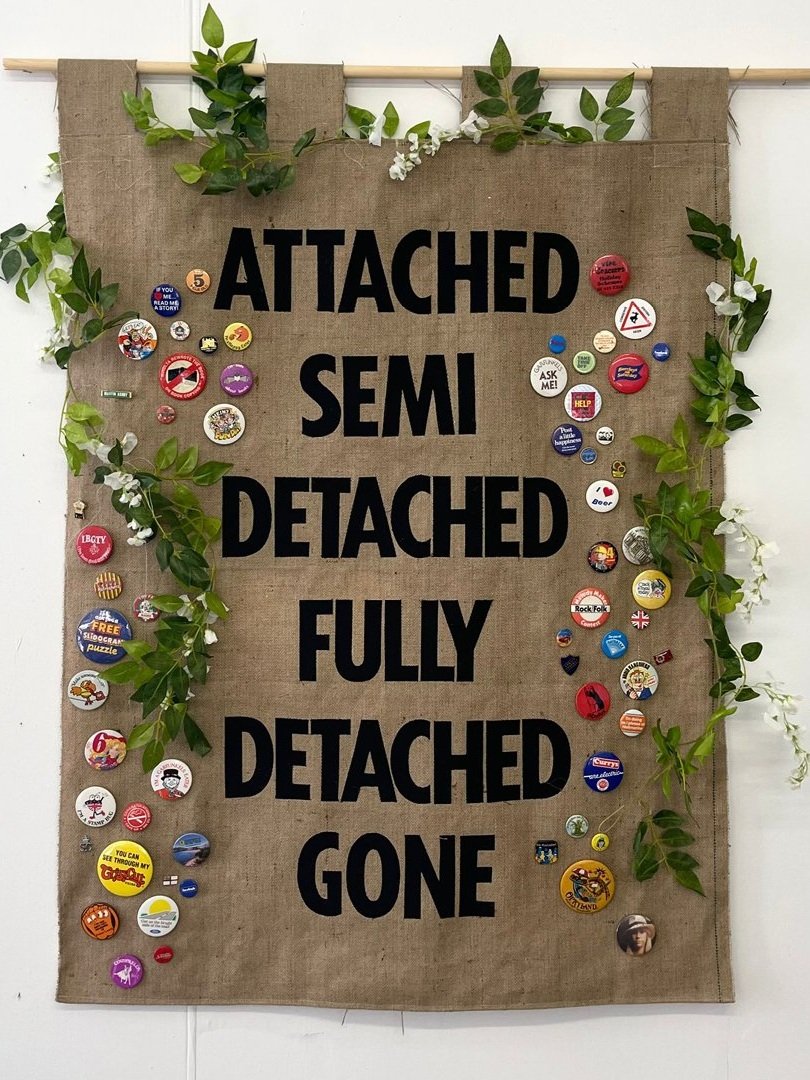

For the exhibition, we’ve recreated a well in the gallery in Hackney which will be a one to one scale replica of that well from my village, which I will dress with a fabric tapestry, which is me commemorating my village and giving back to the land that birthed me. Around the gallery, there will be a series of banners, with short bits of text and a poem I’ve written.

BB: What’s got you so interested in exploring Folk for this show?

CS: There's such a history of Folk being manipulated through the ages because it's pretty unrecorded before the 17th century. No one really knows where some of these things came from, a lot of it is left open to interpretation, people often use it for their own good.

During the 1920s A guy called Cecil Sharp recorded a bunch of Folk songs from around the country that he was using as a way to bolster British pride and hide the injustices that the British Empire had committed overseas. I want to basically use the visual language of Folk to address the myths around rural communities and villages and the sort of the picturesque idyllic world in which people from the cities view villages, and talk about the reality of those communities and how people in those areas often feel marginalised. They're always on the outskirts of somewhere, they're on the edge of the dance floor.

I think when you're growing up in a village, where, you know, the community of old folks, the practice, these traditions have been going on for centuries. They come across quite kooky, and alienating, but at the same time, what you don't realise when you're younger, is that it's quite a wholesome act to give thanks to the land. In the exhibition I’m reflecting on my childhood, I'm being nostalgic, and mourning the loss of my adolescence of being in London. You don't realise what you're in, you live in it, but when you're away from something, you can look at something from a distance and kind of appreciate it and understand it a little bit more.

BB: How did experiencing these Folk traditions first-hand impact you growing up?

CS: There’s a number of things wrapped up in that village lifestyle. The folklore myths around who's doing what, the sort of essence of it is almost a spell, everyone in the village is under this spell. There’s a comfort that village life offers, and that comfort can be quite debilitating, I think, to young people. I think it goes one or two ways really, you can find comfort in the village and never want to leave or you can you can totally reject it. I was always dreaming about getting out and leaving. I always had my eyes set on going to a city. But these villages are essentially places in which people hide from cities. They can have their own little part of London, you know. ‘Keep off my grass’ and ‘Don't knock on my door’ ‘No cold callers’ sort of thing. This exhibition is just one big love letter to my village.

“

I want to use the visual language of Folk to address the myths around rural communities and villages.

“

It's easier for people to believe in this fairytale England of flowers and handkerchiefs and bells.

BB: What have you learnt about Folk in particular that surprised you?

I found out that Cecil Sharp basically went around the country in the early 20th century collecting folk songs from rural communities, he realised he was building an archive and he could reuse them for his own political views. It was quite eye-opening to see how what people think is a real part of history is actually made up in a way. It's a fantasy England, this fantasy world which we've created, the dream England the countryside that people can reside in, and it's easier for people's minds to reside in an England that's comfortable, that they can connect with that idea instead of actually addressing something closer to home.

In my community, the village is an ex-mining community. There's never any talk about the pit that was next to it. Our traditions in our village do not address that pit, the loss of the jobs and what happened to the community after the pits closed. It's easier for people to believe in this fairytale England of flowers and handkerchiefs and bells.

I think Folk distracts us away from the real history of England. We don't see folk traditions talking about the atrocities that the British Empire committed. Britain is great at ignoring its real history, I think a lot of the time it’s happy to pick and choose what it commemorates.

BB: What impression are you hoping viewers of your show will come away with?

I’d like people to think about how England commemorates and creates tradition and ceremony. It sounds bad but the show itself is a bit premature, because in addition to the show I'm going to be working with my local community back home, the parish council and the Morris men of my village to create a new ceremony. I’ll take these banners as a parade at the local carnival we have in the summer, and then dress the well. But I want my ceremony to speak about the realities of what it is like to grow up in one of these communities in one of these villages. I want to kind of put a modern twist, I guess on folk, I want to use the power of folk to make a point about England, and the state of it today.

BB: Why did you decide to do the show now? Did anything in particular drive your curiosity into this?

I don't know what particularly drove me to do this. I'm always reflecting on home and I don't get why I'm so hung up on it. It feels like I'm kind of stuck in the sludge of thinking about this place and how that forms who I am now. All my experiences of who I am now, come from the village that I grew up in, that I disliked so much at the time. I think for myself, it's taught me to be more appreciative of natural things and small things in life. That's how I feel about the community that I grew up in, the village, the people that I grew up around. This show is a commemoration of that, really

“

This exhibition is just one big love letter to my village.

BB: You’ve worked with Guts a few times what can you tell us about your relationship with the gallery?

My relationship with Guts has been an ongoing for about three years now. I think both myself and the gallery have really grown over that time. This exhibition will take place in the new space in Hackney downs, which is a permanent space. Before this exhibition Guts has been a nomadic Gallery, which has only existed online, and has popped up in different spaces.

Guts represents young, emerging artists that haven't been given a chance. They find these young artists that have essentially been ignored by big galleries, and they give them a space and a platform. My relationship with Guts has been a really healthy one for the past three or four years or whatever it's been and I wouldn't be where I am today without it.

BB: Lastly when and where can we see it?

You can see ‘Nowt Is Queer as Folk’ from the 10th of February at Unit 2, Sidings House in Hackney Downs.